insight: The Power of Process

The Power of Process: How Vision Becomes Reality

Design is often judged by its final images. The finished space. The reveal. The photographs that circulate once construction dust has settled. But those outcomes are only possible because of what happens long before a drawing is issued or a finish is selected.

Process is where vision either gains clarity or quietly erodes.

In today’s built environment, projects are more complex than ever. Renovations must respond to existing conditions, evolving codes, community expectations, funding mechanisms, and long-term operational realities. Adaptive reuse and historic rehabilitation introduce additional layers of responsibility, from preservation compliance to public accountability. Yet many projects still rely on a traditional, linear AEC process that assumes alignment will happen along the way.

In practice, it rarely does.

At Reed Walker Design Collective, we believe that thoughtful process is not administrative overhead. It is design strategy. It is risk mitigation. It is an act of care for people, place, and investment. This post offers a deeper look at how our Collective Co-Design process integrates co-creation, design strategy, change management, and historic preservation into a cohesive framework that transforms vision into reality.

A Process 25 Years in the Making

Baby designer Jenna with her work BFF Tamara way back in 2006 at the Fox Tower relighting ceremony

The way we work today did not emerge overnight.

Over the past twenty-five years, my practice has spanned commercial interiors, hospitality, residential design, public and civic projects, academic leadership, historic preservation planning, and time spent working inside development teams. I have collaborated within traditional AEC structures and operated outside of them. I have seen projects succeed because alignment was built early, and I have seen projects struggle because it was assumed alignment would come later.

Early in my career, design often began with a program and a schedule. Stakeholder input was limited. Decisions were made quickly to maintain momentum. When friction emerged, whether between users, owners, budgets, or buildings, it was treated as a problem to solve rather than a signal to pause and listen.

Over time, it became clear that the most successful projects shared a common thread. They invested in understanding before proposing solutions. They acknowledged that buildings are not neutral containers. They recognized that change, even positive change, requires support. And they treated historic structures not as obstacles, but as partners in the process.

The Collective Co-Design process formalizes these lessons. It reframes the designer’s role from service provider to strategic partner and guide. It places alignment before aesthetics and integrates research, narrative, and stewardship into every phase of work.

What Collective Co-Design Really Means

Co-design is often misunderstood as a single workshop or a moment of community engagement. In practice, it is a mindset that shapes how decisions are made from start to finish.

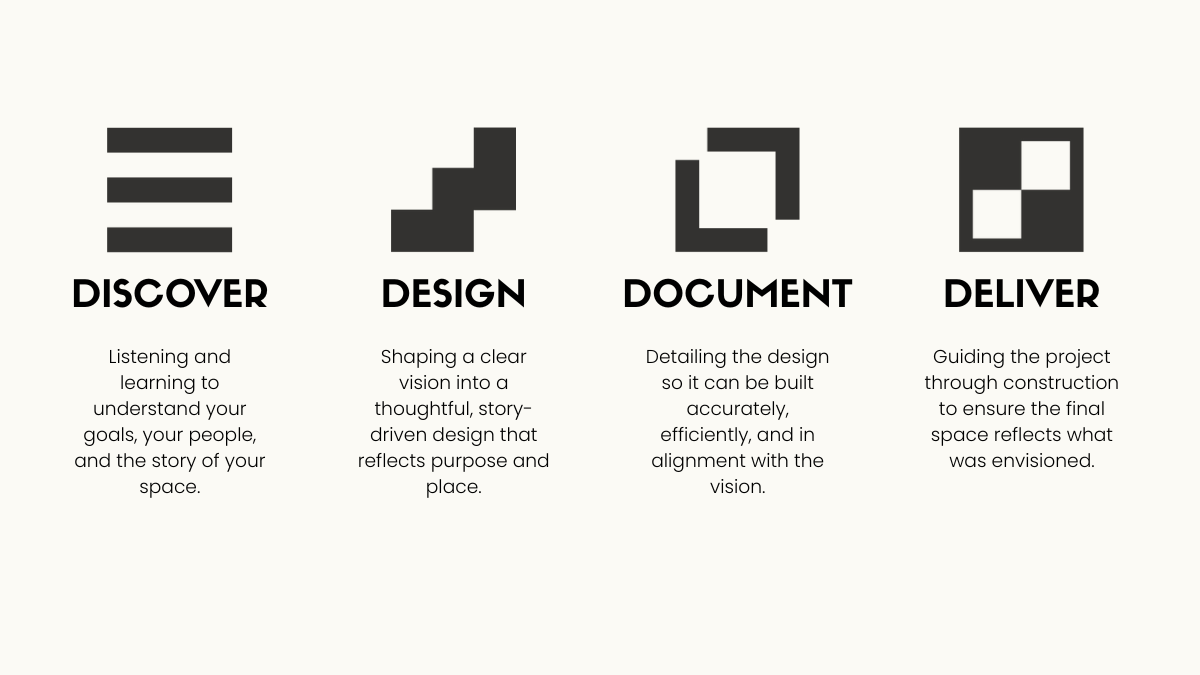

At its core, Collective Co-Design is an integrated system. It combines four interdependent phases: Discover, Design, Document, and Deliver. Each phase builds on the one before it, ensuring continuity between vision, execution, and experience.

What makes this approach different is not the presence of these phases, most design processes have them. It is how intentionally they are connected, and how strategy, change management, and preservation are woven throughout rather than treated as separate scopes.

Discover: Building Alignment Before Design Begins

Every project begins with listening.

The Discover phase is dedicated to understanding the full context of a project before design direction is established. This includes physical conditions, historical layers, cultural dynamics, operational needs, economic realities, and the lived experiences of the people who will use the space.

Discovery often includes stakeholder interviews, staff and community listening sessions, site visits, behavioral observations, and archival research. We look for patterns, tensions, and shared priorities. We ask questions that move beyond square footage and adjacency, questions about identity, memory, and aspiration.

For historic properties, this phase is especially critical. We identify periods of significance, assess preservation eligibility, and evaluate whether federal or state historic tax credits may be part of the funding strategy. When applicable, we align early decisions with the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation from the outset, rather than retrofitting compliance later.

The outcome of Discovery is not a concept. It is clarity. A shared understanding of purpose, constraints, and opportunity. When alignment is built early, projects move forward with greater confidence and fewer costly corrections.

Design: Where Strategy, Story, and Space Converge

Design is often described as a creative act, and it is. But creativity without direction leads to drift.

During the Design phase, insights gathered in Discovery are translated into a clear narrative and spatial strategy. Narrative here is not branding language added after the fact. It is a decision-making framework that guides priorities, trade-offs, and investment.

Co-design in this phase may include visioning workshops, furniture testing, full-scale mockups, scenario planning, and iterative feedback loops with stakeholders. These moments are not about consensus for its own sake. They are about informed participation and shared ownership of the outcome.

Change management is also active during this phase. Renovations, rehabilitations, or moving to a new space affect routines, identities, and expectations. Even when change is welcome, it can create uncertainty. Clear communication, milestone alignment, and education help support residents, staff, boards, and community members through the transition.

When design is grounded in strategy and supported by engagement, decision-making becomes more efficient. Teams spend less time revisiting fundamentals and more time refining solutions that truly serve the project’s goals.

Document: Turning Vision into Buildable Reality

Documentation is where many projects lose their original intent.

As drawings become more technical, there is a risk that the underlying narrative is reduced to a series of specifications. Our role during this phase is to ensure that strategy, story, and preservation requirements remain visible and intact.

We coordinate closely with architects, engineers, and consultants to align details, materials, and assemblies with the agreed vision. For historic projects, this includes careful review of materials and detailing to ensure compliance with preservation standards and tax credit requirements.

When preservation is addressed early, documentation becomes a tool for clarity rather than compromise. Contractors are better informed, bids are more accurate, and the likelihood of redesign during construction is significantly reduced.

Deliver: Stewardship Through Construction and Completion

The final phase of the process is about advocacy.

During construction and installation, we remain actively engaged to protect the integrity of the design. This includes reviewing submittals, responding to design-related questions, and supporting contractors with clarity and context.

For clients who select FFE administration or procurement services, continuity extends through furniture, lighting, artwork, and accessories. These final layers are not decorative afterthoughts. They are integral to how a space functions and feels.

Stewardship during this phase ensures that what was envisioned is what is experienced. It reinforces trust and accountability across the project team and delivers a space that feels intentional rather than diluted.

Where Historic Preservation Tax Credits Fit IN

Historic preservation incentives can be transformative, but only when they are integrated thoughtfully.

Too often, tax credit requirements are introduced late in the process, forcing redesign, budget strain, or difficult compromises. In our process, preservation considerations inform early decisions, shaping narrative, materials, and scope from the beginning.

A strong story grounded in history and community benefit strengthens tax credit applications and public support. More importantly, it ensures that preservation is not about freezing a building in time, but about guiding its next chapter responsibly.

When preservation is treated as strategy rather than restriction, it becomes a catalyst for both economic viability and long-term relevance.

Collective Co-Design Versus the Traditional AEC Model

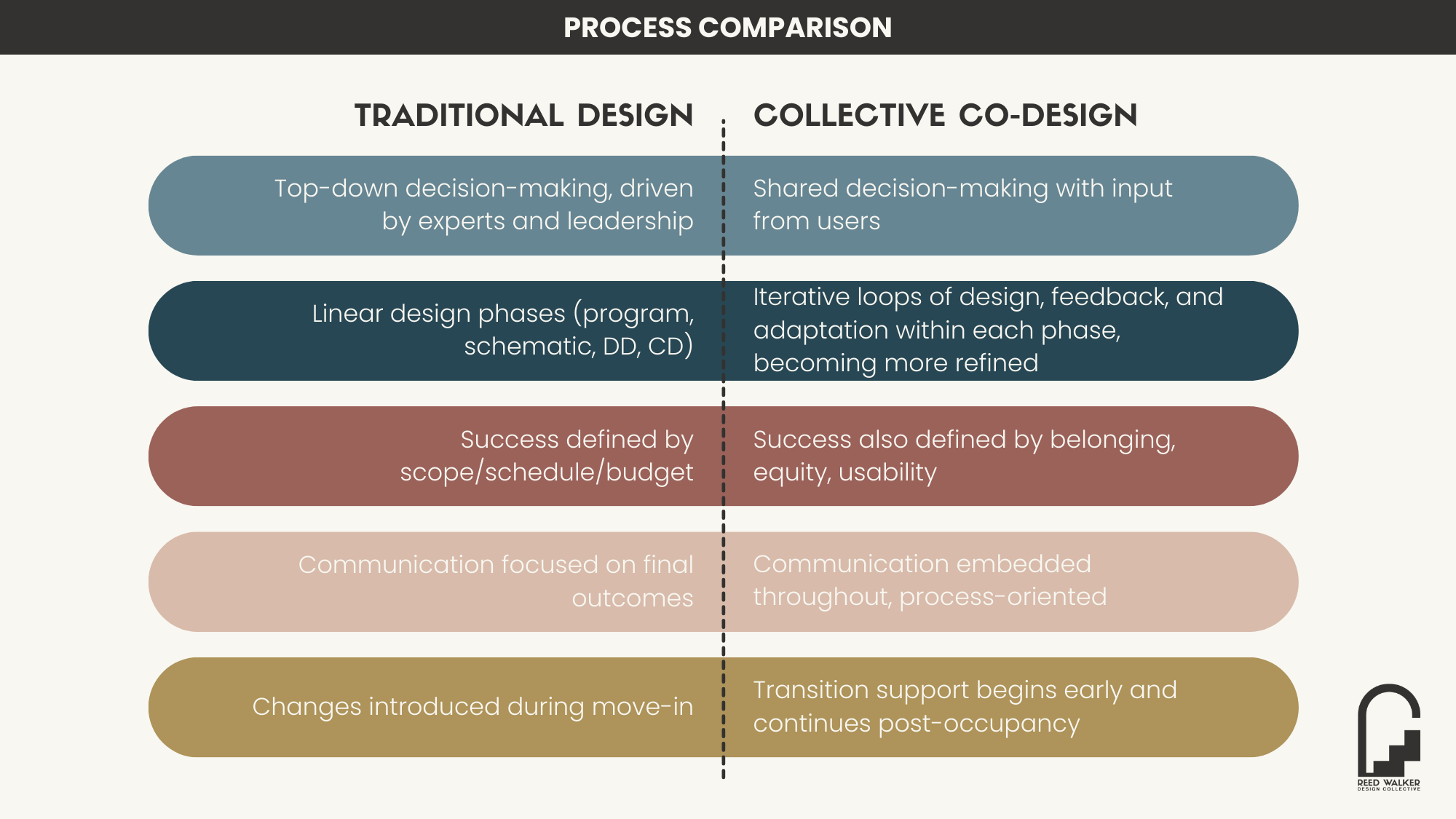

The differences between this approach and a traditional AEC process are significant.

In a conventional model, projects often move linearly from programming to design to documentation, with limited feedback loops. Stakeholder engagement is reactive. Preservation and incentives are addressed as constraints. Change is managed through course correction.

Collective Co-Design is iterative and integrated. Alignment precedes design. Stakeholders are partners, not obstacles. Preservation informs early decisions. Change is anticipated and supported.

Why This Process Leads to Better Outcomes

Projects shaped by intentional process experience fewer costly revisions, clearer decision-making, and stronger buy-in from the people they serve. They age better because they are grounded in context rather than trend. They feel cohesive because every decision traces back to a shared understanding of purpose.

Most importantly, they respect the complexity of real places and real people.

Process as a Form of Care

Design does not begin with drawings. It begins with listening.

Want More Insights?

Our Spring Edition of the Insight Newsletter arrives in March, featuring:

new year reflections

design insights for the season ahead

behind the scenes on our projects

upcoming speaking events

Sign up HERE

Be well,

Jenna